Close to the heart.

The ballad has always enjoyed a direct relationship to music. After all, its modern forebears were musicians – the Provencal troubadour song-poets and courtly folk musicians. So, its evolution as a form features line structure and rhythms that, like its subjects, stick close to the heart.

Classic beats.

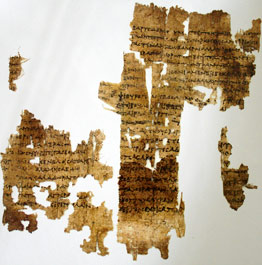

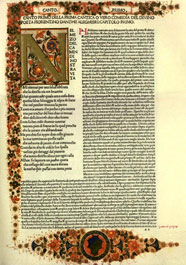

Among the first written forms of ballad were the Italian ballata and Spanish ballade, which traversed royal courts and countrysides in the 13th century. A ballata by pre-Renaissance poet Guido Cavalcanti clearly illustrates the classic 4-3-4-3 beat of the balladic quatrain.

Ballata 5

Guido Cavalcanti (1255-1300)

Light do I see within my Lady’s eyes

And loving spirits in its plenisphere

Which bear in strange delight on my heart’s care

Till Joy’s awakened from that sepulchre.

That which befalls me in my Lady’s presence

Bars explanation intellectual.

I seem to see a lady wonderful

Spring forth between her lips, one whom no sense

Can fully tell the mind of, and one whence

Another, in beauty, springeth marvelous,

From whom a star goes forth and speaketh thus:

"Now my salvation is gone forth from thee."

There where this Lady’s loveliness appeareth,

Is heard a voice which goes before her ways

And seems to sing her name with such sweet praise

That my mouth fears to speak what name she beareth,

And my heart trembles for the grace she weareth,

While far in my soul’s deep the sighs astir

Speak thus: "Look well! For if thou look on her,

Then shalt thou see her virtue risen in heaven."

The commoners’ alternative.

By the 15th century, the easy-to-write ballad served as a commoners’ alternative to the more formal, courtly sonnet and the more complex rondeau, and ballads were being written in England, France, Spain, Italy, and Germany. French poet Francois Villon’s "Ballad of the Gibbet" shows another direction ballads often took: that of imparting wisdom to readers and listeners.

Ballad of the Gibbet

Francois Villon (1431-1489)

Brothers and men that shall after us be,

Let not your hearts be hard to us:

For pitying this our misery

Ye shall find God the more piteous.

Look on us six that are hanging thus,

And for the flesh that so much we cherished

How it is eaten of birds and perished,

And ashes and dust fill our bones’ place,

Mock not at us that so feeble be,

But pray God pardon us out of his grace.

Listen we pray you, and look not in scorn,

Though justly, in sooth, we are cast to die;

Ye wot no man so wise is born

That keeps his wisdom constantly.

Be ye then merciful, and cry

To Mary’s Son that is piteous,

That his mercy take no stain from us,

Saving us out of the fiery place.

We are but dead, let no soul deny

To pray God succor us of His grace.

The rain out of heaven has washed us clean,

The sun has scorched us black and bare,

Ravens and rooks have pecked at our eyne,

And feathered their nests with our beards

And hair.

Round are we tossed, and here and there,

This way and that, at the wild wind’s will,

Never a moment my body is still;

Birds they are busy about my face.

Live not as we, not fare as we fare;

Pray God pardon us out of His grace.

L'envoy

Prince Jesus, Master of all, to thee

We pray Hell gain no mastery,

That we come never anear that place;

And ye men, make no mockery,

Pray God, pardon us out of His grace.

Ballad of the Cool Fountain

Anonymous Spanish poetess (15th century)

Fountain, coolest fountain,

Cool fountain of love,

Where all the sweet birds come

For comforting–but one,

A widow turtledove,

Sadly sorrowing.

At once the nightingale,

That wicked bird, came by,

And spoke these honied words:

"My lady, if you will,

I shall be your slave."

"You are my enemy:

Begone, you are not true!

Green boughs no longer rest me,

Nor any budding grove.

Clear springs, where there are such,

Turn muddy at my touch.

I want no spouse to love

Nor any children either.

I forego that pleasure

And their comfort too.

No, leave me; you are false

And wicked–vile, untrue!

I’ll never be your mistress!

I’ll never marry you!"

While oration was always part of the balladic form – the heart of Spain’s oral poetry tradition, in fact – English poets created truly plot-driven narrative ballads meant for reading. An early example is Sir Walter Raleigh’s "As You Came From The Holy Land," believed to be derived from a well-told medieval oral folk tale. Note the narrative quality and the detachment of the writer.

From As You Came from the Holy Land

Sir Walter Raleigh (1552?-1618)

"As you came from the holy land

Of Walsinghame,

Met you not with my true love

By the way as you came?"

"How shall I know your true love,

That have met many one

As I went to the holy land,

That have come, that have gone?"

"She is neither white nor brown,

But as the heavens fair,

There is none hath a form so divine

In the earth or in the air."

"Such an one did I meet, good Sir,

Such an angelic face.

Who like a queen, like a nymph, did appear

By her gait, by her grace."

"She hath left me all alone,

All alone as unknown.

Who sometimes did lead me with herself,

And me loved as her own."

"What’s the cause that she leaves you alone

And a new way doth take,

Who loved you once as her own

And her joy did make?"

"I have loved her all my youth,

But now old as you see,

Love likes not the falling fruit

From the withered tree."

The ballad’s storytelling power.

By the time of the Romantic poets, ballad was as familiar to English readers as the novel is to readers today. The Romanticists used that familiarity to their advantage and perfected both the art and storytelling power of the ballad. Out of countless great ballads came the immortal "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner."

From The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834)

It is an ancient Mariner,

And he stoppeth one of three.

"By thy long gray beard and glittering eye,

Now wherefore stopp'st thou me?

The Bridegroom’s doors are opened wide,

And I am next of kin;

The guests are met, the feast is set:

May'st hear the merry din."

He holds him with his skinny hand,

"There was a ship," quoth he.

"Hold off! Unhand me, gray-beard loon!"

Eftsoons his hand dropt he.

He holds him with his glittering eye–

The Wedding-Guest stood still,

And listens like a three years’ child:

The Mariner hath his will.

The Wedding-Guest sat on a stone:

He cannot choose but hear;

And thus spake on that ancient man,

The bright-eyed Mariner.

The ship was cheered, the harbor cleared,

Merrily did we drop

Below the kirk, below the hill,

Below the lighthouse top.

Playing with structure.

Some Romantic poets experimented with the ballad’s core structure, finding the quatrain too restrictive for their elaborate stories. Byron hit upon the double-quatrain – an eight-line stanza – and wrote a broadside at fellow Romanticists Robert Southey and William Wordsworth that offers insight into the rivalries that existed among the greats of the time:

From Don Juan

Southey and Wordsworth

George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788-1824)

Bob Southey! You’re a poet–Poet laureate,

And representative of all the race;

Although 'tis true that you turned out a Tory at

Last–yours has lately been a common case;

And now, my Epic Renegade! What are yet at?

With all the Lakers, in and out of place?

A nest of tuneful persons, to my eye

Like "four and twenty Blackbirds in a pye;

"Which pye being opened they began to sing"

(This old song and new simile holds good),

"A dainty dish to set before the King;"

Or Regent, who admires such kind of food;–

And Coleridge, too, has lately taken wing,

But like a hawk encumbered with his hood–

Explaining metaphysics to the nation–

I wish he would explain his Explanation…

And Wordsworth, in a rather long "Excursion"

(I think the quarto holds five hundred pages),

Has given a sample from the vasty version

Of his new system to perplex the sages;

'Tis poetry–at least by his assertion,

And may appear so when the dog-star rages–

And he who understands it would be able

To add a story to the Tower of Babel.

You–Gentlemen! by dint of long seclusion

From better company, have kept your own

At Keswick, and through still continued fusion

Of one another’s minds, at last have grown

To deem as a most logical conclusion,

That poesy has wreaths for you alone;

There is a narrowness in such a notion,

Which makes me wish you’d change your lakes for ocean.

The early 20th century’s preeminent balladeer, W.B. Yeats, also preferred the eight-line stanza:

The Second Coming

William Butler Yeats (1865-1939)

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?