Seeing the consciousness forest for the trees

https://iai.tv/articles/seeing-the-consciousness-forest-for-the-trees-auid-2901?_auid=2020

EXCERPTS: The American public intellectual and creator of the television series Closer to Truth, Robert Lawrence Kuhn has written perhaps the most comprehensive article on the landscape of theories of consciousness in recent memory. In this review of the consciousness landscape, Àlex Gómez-Marín celebrates Robert Kuhn’s rejection of the monopoly of materialism and uncovers the radical implications of these new accounts of consciousness for meaning, artificial intelligence, and human immortality.

[...] The origins of our perplexity in making sense of experience itself can be traced back to Galileo Galilei, who programmatically excluded subjective experience from the purview of science...

[...] Such a strategy proved tremendously successful, giving rise to physics, then chemistry, next biology, and finally psychology. ... Four hundred years later, we can’t ignore the elephant in the room anymore: experience is what makes science possible and yet a proper science of consciousness seems unattainable. The Galilean knot remains untied. Today we call it “the hard problem”.

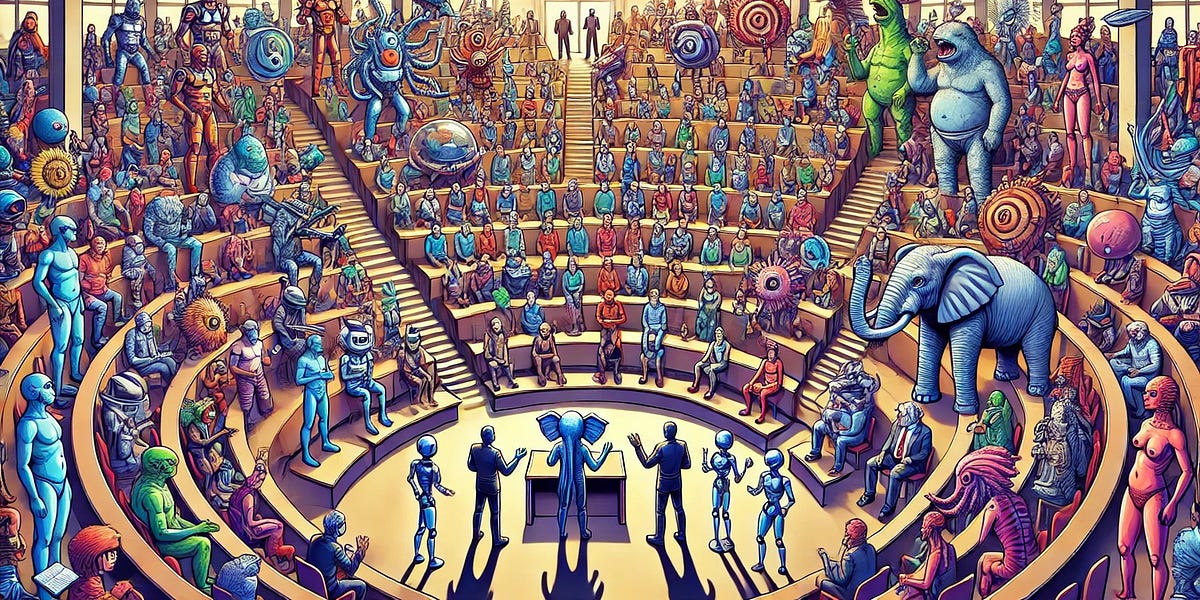

[...] Gathering under the same roof most of the greatest contemporary thinkers of one of the greatest questions one can ever try to answer, Kuhn’s landscape enacts the quasi-extinct art of true scholarship...

[...] The landscape comprises 10 major categories and it is organised in a gradient of “isms”, from die-hard materialist positions to mind-only propositions...

[...] Kuhn’s faithful description of each position without the urge to adjudicate deserves nothing but praise and gratitude. ... Rather than divide and conquer, let us unite and wonder... (MORE - missing details)

PAPER (Kuhn): A landscape of consciousness: Toward a taxonomy of explanations and implications

_

https://iai.tv/articles/seeing-the-consciousness-forest-for-the-trees-auid-2901?_auid=2020

EXCERPTS: The American public intellectual and creator of the television series Closer to Truth, Robert Lawrence Kuhn has written perhaps the most comprehensive article on the landscape of theories of consciousness in recent memory. In this review of the consciousness landscape, Àlex Gómez-Marín celebrates Robert Kuhn’s rejection of the monopoly of materialism and uncovers the radical implications of these new accounts of consciousness for meaning, artificial intelligence, and human immortality.

[...] The origins of our perplexity in making sense of experience itself can be traced back to Galileo Galilei, who programmatically excluded subjective experience from the purview of science...

[...] Such a strategy proved tremendously successful, giving rise to physics, then chemistry, next biology, and finally psychology. ... Four hundred years later, we can’t ignore the elephant in the room anymore: experience is what makes science possible and yet a proper science of consciousness seems unattainable. The Galilean knot remains untied. Today we call it “the hard problem”.

[...] Gathering under the same roof most of the greatest contemporary thinkers of one of the greatest questions one can ever try to answer, Kuhn’s landscape enacts the quasi-extinct art of true scholarship...

[...] The landscape comprises 10 major categories and it is organised in a gradient of “isms”, from die-hard materialist positions to mind-only propositions...

[...] Kuhn’s faithful description of each position without the urge to adjudicate deserves nothing but praise and gratitude. ... Rather than divide and conquer, let us unite and wonder... (MORE - missing details)

PAPER (Kuhn): A landscape of consciousness: Toward a taxonomy of explanations and implications

_